Visualization Techniques for the Pianist

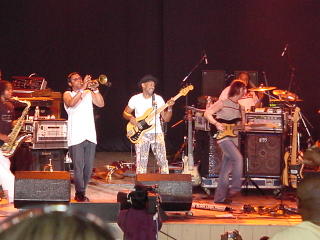

Cell Phone "photo image" Captured July 25, 2005 at the U.S. Library of Congress. This reception was sponsored by the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, in Commemoration of the Civil Rights Voting Act of 1965.

Controlling the images of the mind through image projection has proven valuable not only for psychotherapy, but also as a learning aid.

Visualization can have as much impact on the subconscious, memory, and entire body as a "real" experience.

For example, it is sometimes more expeditious to memorize a song by reading and thinking it through than it is to play it. Some musicians like to work on a difficult passage by visualizing themselves playing it with perfect execution and technique. When visualizing, energy is channeled and concentration is pinpointed. The mind, and sometimes even the muscles will react and learn as if the music was actually being played.

I'm not suggesting you sell your instrument and spend all of your time meditating, but visualization is a means to very fast results.

Having negative thoughts or feelings about ourselves produces negative results. This is true even when we are unaware of the thoughts and feelings we are having. The first step for visualizing is to become aware of how you "program" yourself, that is what you "tell yourself," about your musical abilities and the way you play. The next step is to learn how visualization works. You can put it to work for you as a tremendous aid for learning, playing, or anything you choose.

The imagination is one of the main taps of our subconscious. The subconscious is the controlling force behind creativity. We are all in a never ending process of creating. (One guy I know has 11 kids.) We are creating our perception of life, creating our happiness or misery or whatever we choose. The more control we have over our creative resources, the better our music and more fulfilling our lives will be.

We can get the creative wheels turning, by relaxing and changing our state of mind. Deep breathing (also known as diaphramic breathing) the foundation of vocalizing is commonly used by musicians before playing and before going on stage. It relaxes the entire body and slows down the brain waves, which allows for clearer thinking. Uncontrolled nerves (as any singer knows) are a hindrance, especially to improvisation and songwriting, where a relaxed "letting go" attitude is necessary.

The reason that some days you're hot and some you're not is your changing frame of mind. A little mind control makes for a more consistent player and more rapid improvement.

For additional resources, visit: www.mrronsmusic.com/playpiano.htm